| |

|

|

| ▲ Jin Kwon Hyun Ceo of center for free enterprise |

This paper is prepared for the presentation at the 70th Congress of the International Institute of PublicFinance, which is held at Lugano, Switzerland during August 20~23, 2014.

Abstract

Our main concern is to examine the impact of economic freedom on the level of shadow economy by using country level data in 1997. As economic freedom is mostly determined by legal and administrative regulation, we include these two factors to explain the level of shadow economy. As expected, both regulations of law and administration have the positive effect on shadow economy. Thus our empirical evidence suggests that one important policy direction to decrease the level of shadow economy would be legal and administrative deregulatory policies, which will lead to higher levels of economic freedom.

Key words: Economic freedom, Shadow economy, Regulation

1. Introduction

There have been many studies to examine the level of tax compliance or shadow economy. On a superficial level, economic factors such as tax audit and penalty rates had been theoretically and empirically examined. On a deeper level, non-economic factor, including tax morale and culture, was empirically studied. Subsequently, several studies in tax compliance have tried to find new determinant of tax compliance. Recently, institutional factors as non-economic factors, such as democracy, political and legal stability, etc. have been other elements to empirically explain tax compliance or shadow economy. For example, Torgler and Schneider (2010, 2009), Torgler (2005), Torgler, et al. (2007).

Economic freedom might be one determinant of tax compliance and shadow economy. As regulation restricts economic activities by allowing less economic freedom, it inevitably leads to hiding and cheating of economic outcomes by economic agents. Thus, we easily infer that economic freedom is one important factor to explain the level of shadow economy. However, empirical studies to examine this conjecture have been very few.

The purpose of this study is to empirically examine the effect of economic freedom on the level of shadow economy using country level data. We hope that the study takes us one step closer to find yet another determinant of tax compliance or shadow economy. Our study is structured as follows: In Section 2, we review the trend of researches on tax compliance. In Section 3, empirical model and results are shown, and in Section 4, we conclude this study.

2. Literature review on tax compliance

Based on the seminal work of Allingham and Sandmo (1972), taxpayers' behaviour in terms of compliance has been explained mainly by the game theory. Refer to Andreoni, Erard, and Feinstein (1998), Alm (1999), Fisher, Wartick, and Mark (1992), and Slemrod (1992) for the survey about tax compliance in general.

Taxpayers would usually maximize the expected utility, in spite of minor differences across differing models, under the constraints in which a tax authority controls the two policy tools of tax audit and penalty rate.

Those two (economic) controlling instruments, which are the proportion of audited taxpayers with respect to the entire body of taxpayers, and the penalty rate for evaded taxes imposed upon audit, respectively, have generally been found to be effective in deterring tax evasion. For example, it is theoretically explained in Boyd (1986) that the punishment-oriented policy utilizing a tax audit and a penalty rate is effective. Also, Dubin and Wilde (1988) and Park and Hyun (2003) show empirical evidence of the effectiveness of a tax audit in terms of preventing tax evasion.

Over time, the study of tax compliance, in order to give a fuller explanation on the compliant behaviour of taxpayers, has subsequently been extended to include other economic or non-economic factors such as tax education, morale, tax culture, etc. For example, Alm, McClelland, and Schulze (1992) studied the effect of provision of public goods by government, and Alm, Bahl, and Murray (1990) investigated the tax structure including tax rates. Nagin (1990) provides a comprehensive review of those factors studied up the 1980s. More recently, investigations with regard to tax morale or tax culture, which was conventionally neglected in economics, have been started by Torgler (2004, 2005).

In particular, we note that there has been a great deal of empirical studies on the effect of tax morale worldwide in the 2000s. Alm and Torgler (2006) used the World Value Survey data from 17 countries, and Torgler, et al. (2008) utilized micro datasets of the U.S. and Turkey followed by the Italy’s household data in Lubian and Zarri (2011). Alm and Torgler (2011) presented a comprehensive examination of the existing stock of such literature on tax morale. Very recently, Alm and McClellan (2012) confirmed its importance for the business sector through the data consisting of 8,500 firms across 34 countries. Along with this literature emphasizing the role of tax morale, researchers have also started investigating its determinants, such as institutions and cooperation networks in Alm and Gomez (2008) and changes in the political and fiscal system in Martinez-Vazquez and Torgler (2009).

In addition to tax morale, institutional factors including government quality, political stability and rule of law are other determinants of tax compliance. As institutional factors are highly correlated with tax morale, the effect of tax morale can be implicitly assumed to reflect the impact of institutional factors. Torgler, et al. (2007) show the empirical evidence by using experimental and survey data that institutional factors affects the level of tax morale, and eventually tax morale has impact on tax compliance. Torgler (2005) also shows the positive impact of direct democracy on tax morale in Switzerland using survey data. Torgler, et al. (2010) analyze the relevance of local autonomy on tax morale and compliance in Switzerland, and find the positive relationship between local autonomy and tax morale and the negative one between local autonomy and tax compliance.

Torgler and Schneider (2009) explain the level of shadow economy in the world, by using tax morale and institutional factors as independent variables together. Those studies, even though they have slightly different approaches among tax compliance, tax morale, and institutional factors, consistently show that there is impact of institutional factors on tax compliance.

We assume that economic freedom might be another determinant of the level of tax compliance or shadow economy. It can be easily inferred that as a society has higher levels of economic freedom, the tax compliance might be higher. People and the executive administration in a highly regulated society by law might have tendency to cheat and hide their economic activities and outcomes.

3. Empirical Analysis

We empirically examine the impact of economic freedom on shadow economy by using the ‘Economic Freedom of the World’ data by Gwartney and Lawson (2009). Although the level of economic freedom is determined by many different factors, our main interest focuses on the institutional factors. As the level of economic freedom is conceptually too abstract, it is difficult to derive some policy implication from empirical estimates. Thus we choose the institutional factors which consist of the different levels of economic freedom. Institutional factors are highly related to regulations by law as well as executive administration. Therefore, we choose two factors to examine their impact on shadow economy. One is regulation by law, and the other is administrative regulation.

| |

|

|

| |

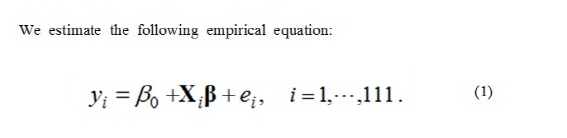

(1)In equation (1), vector includes two core explanatory variables especially pertinent to the level of economic freedom with other control variables. For the dependent variable, , we use the ‘ratio of shadow economy size to GDP (%)’ estimated by Buehn and Schneider (2011) for 162 countries in 1997. However, in the process of combining other datasets coupled with a few missing values, the number of observation reduced to 111. Also, we used the statistics of 2007 because this was the most recent year in Buehn and Schneider (2011).

Variations were substantial from8.1(Switzerland) to 63.5(Bolivia) with the mean of 29.8.

Table 1 reports the OLS estimation results of equation (1). First, two control variables are employed sequentially. Eq.1 includes which takes one if the country is an advanced country by the standard of IMF as of 2007 (i.e., 30 out of 111 countries), or zero otherwise. Advanced countries significantly (at the 1 percent level) have a lower level of shadow economy with a substantial coefficient estimate in absolute terms. The is relatively high considering there is only a single explanatory variable. In Eq. 2, we attempted to organize the regional effect with different groupings, such as Europe, Asia, Africa, and America. The coefficient estimates of countries in Europe and Asia tend to have negative signs, but are not statistically significant as shown in Table 1. However, these regional variables hardly affect the statistical performance of.

In Eq.3, we added LEG_STABILITY, the index of ‘Legal Structure and Security of Property’ that was used to measure the ‘Economic Freedom of the World(EFW)’ by Gwartney and Lawson(2009). One of the components in EFW, the ‘Legal Structure and Security of Property Rights’ used for our analysis consists of the following critical subcomponents: judicial independence, impartial courts, protection of property rights, military interference in rule of law and the political process, integrity of the legal system, legal enforcement of contracts, and regulatory restrictions on the sale of real property.

The values of, range from zero to (the highest possible rating) ten, are similar to the other indices in EAW. The distribution of was diverse from 1.99 to 9.05 with the mean of 5.93.

As shown in Table 1, the coefficient estimate of LEG_STABILITY is negative and highly significant at the 1% level. The reduced coefficient of ADVANCED in absolute terms in Eq.3 suggests that part of the explanatory power of the variable in Eq.1 and Eq.2 was in fact due to the usual legal environment of the advanced countries. However, our testing revealed that there is no sign of multicollinearity from adding LEG_STABILITY. Note also that the rose substantially by approximately 0.1 up to 0.4866, indicating these two variables alone explain a sizable portion of the variance in the level of shadow economy across 111 countries.

In Eq.4, from the aforementioned EFW, we include, BUREAUC_COST, the index ‘focusing on regulatory (or administrative) restraints that limit the freedom of exchange in credit, labor, and product markets.’ We suggest that this explanatory variable can capture the overall bureaucratic cost caused by their power in law-making and also their actual enforcement of the law. The mean of BUREAUC_COST is 4.49 with a large variation from 1.10 to 7.07. The coefficient estimate of BUREAUC_COST has the expected positive sign at the 5% level. Note that inclusion of this variable slightly lowers the significance level of the LEG_STABILITY coefficient (with the p-value of 0.068 now) and also reduces its size in absolute terms. This result is believed to be due to the fact that the aforementioned subcomponents constituting LEG_STABILITY do not sufficiently capture the discretionary power of regulatory administration.

4. Conclusions

There have been so many studies to examine what determines the level of tax compliance. At the beginning stage of research, economic factors, especially tax audit and penalty rate, etc., were examined to explain the tax compliance. Moreover, non-economic factors such as tax morale and culture were also studied. Recently, institutional factors have been focused for empirical, including political stability, government quality, regulation, etc. We empirically examine the impact of economic freedom, as one of institutional factors, on the level of shadow economy by using country level data in 1997. As economic freedom is mostly determined by legal and administrative regulation, we include these two factors to explain the level of shadow economy.

As expected, both regulations of law and administration have the positive effect on shadow economy. We interpret that the level of economic freedom is the another determinant of the shadow economy. Thus our empirical evidence suggests that one important policy direction to decrease the level of shadow economy would be legal and administrative deregulatory policies, which will lead to higher levels of economic freedom. Of course, we need to have more researches to illuminate their impact on shadow economy, especially by using the individual level data. We remain this approach for further studies. /Jin Kwon Hyun, Ceo of Center for Free Enterprise, Iljoong Kim professor of sungkyunkwan University.